Refugees & Citizens of The Earth

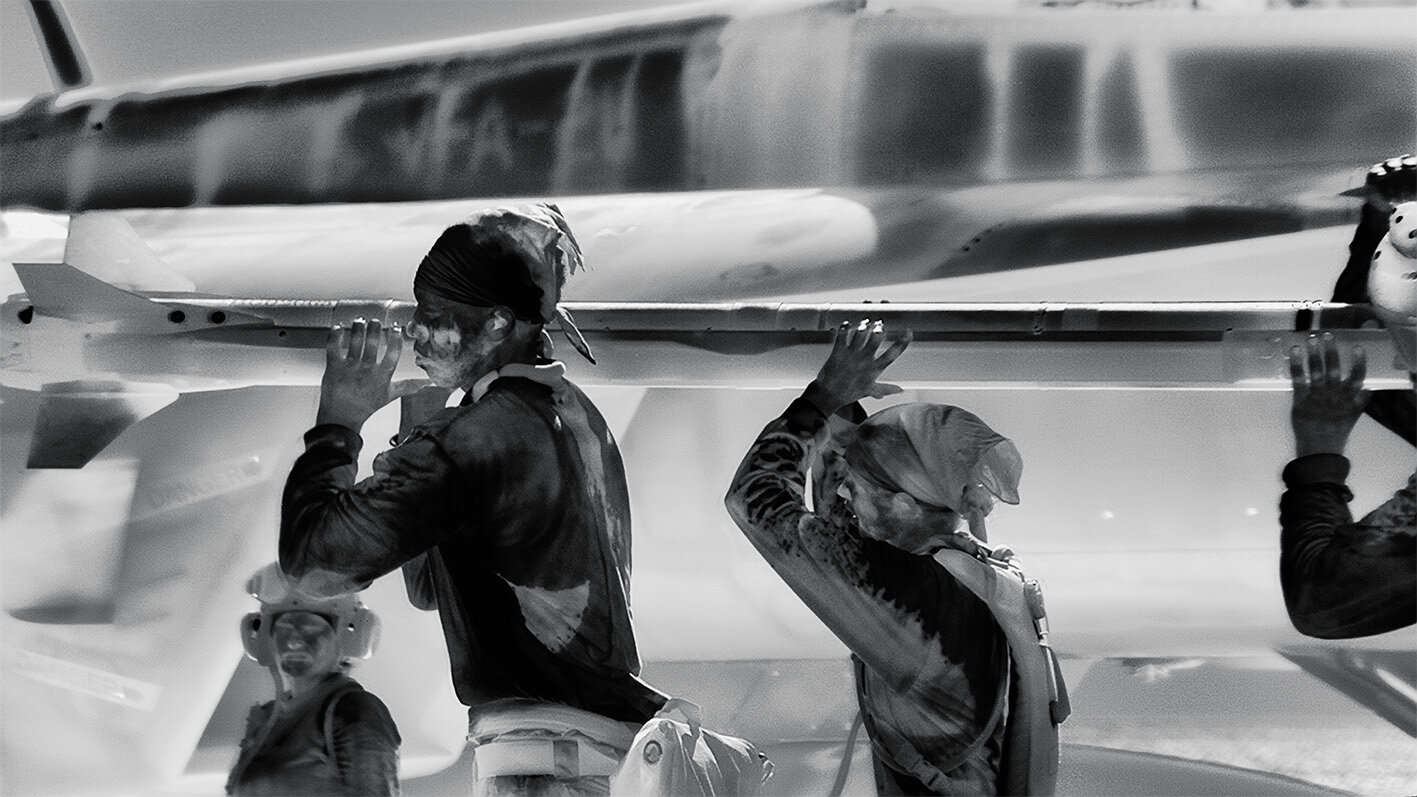

Photography series : Incoming by Richard Mosse

Soundtrack recorded by Lupus (The Judgement Hall Records) using compositions by Jose Macabra - The Eye of The Beholder & London is Dead.

The soundtrack portrays the perilous journey of migrants across the Mediterranean trafficking routes.

“In a sea of human beings, it is difficult, at times even impossible, to see the human as being.”

― Aysha Taryam

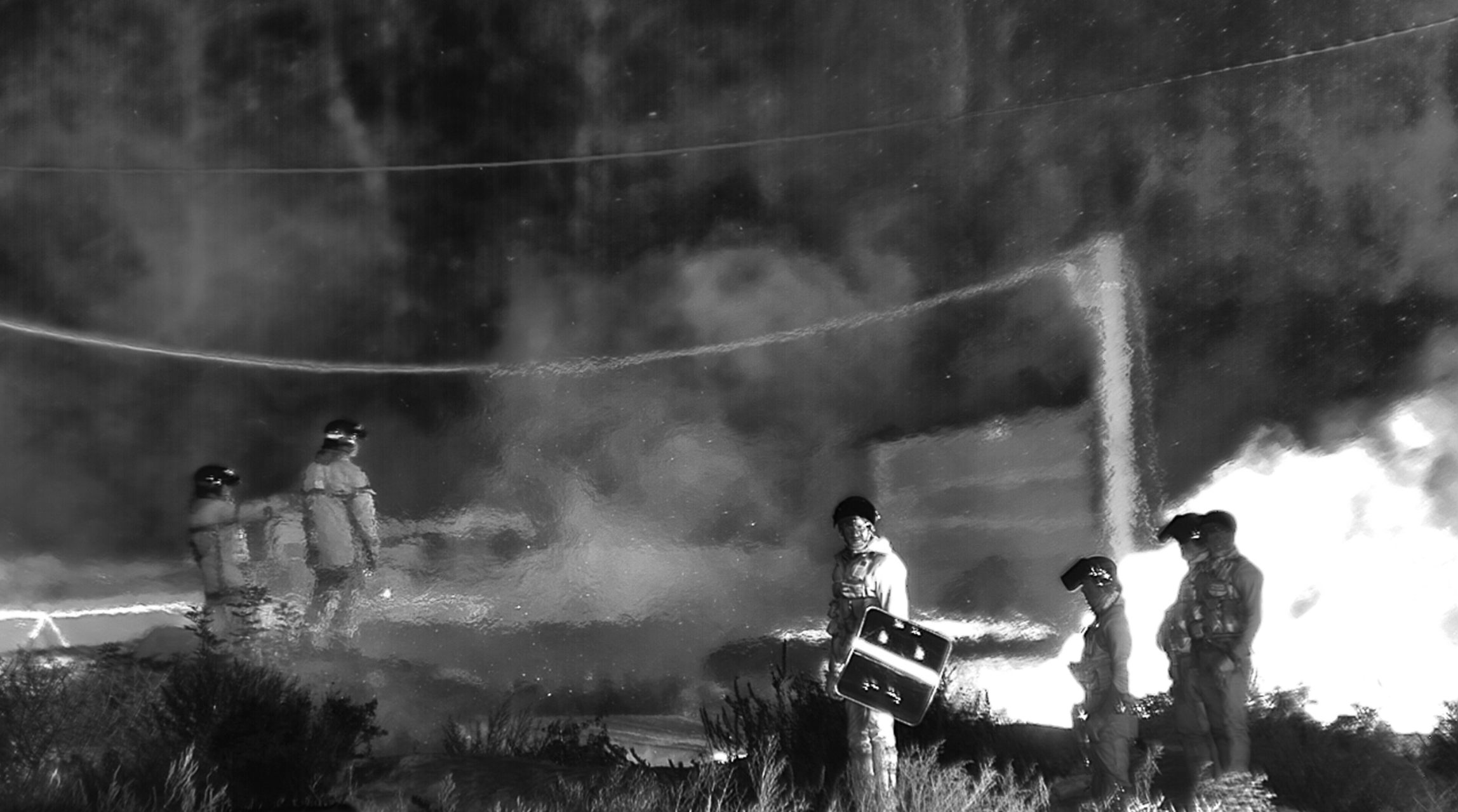

Incoming charts mass migration and human displacement unfolding across Europe, the Middle East and North Africa. War, persecution, climate change, and other factors have contributed to the largest migration of people since WWII.

Incoming intercepts two of the busiest and most perilous routes. One from the east, from countries such as Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan, crossing Turkey, and arriving in the EU on the shores of Aegean islands, then passing through the Balkan corridor on the route north. The other is from the south, from countries in the Sahel region – Senegal, Mali, Nigeria, Niger, Chad, Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea – crossing the Sahara Desert for Libya, where they attempt to cross the Mediterranean hoping to reach Italy, often continuing north for countries such as France, Germany, the UK, and other wealthy nations.

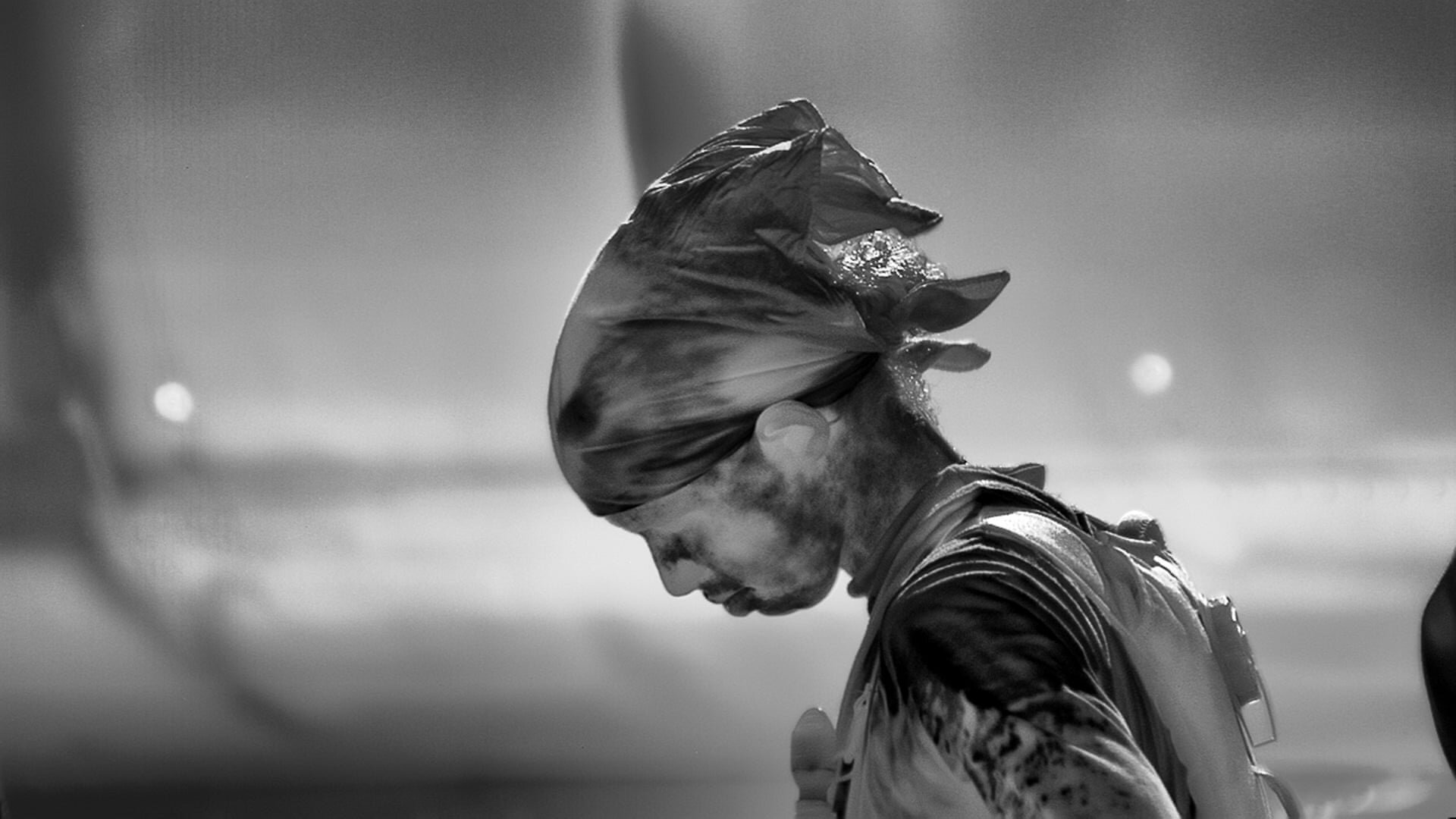

"I used a military-grade camera designed for battlefield situational awareness and long-range border surveillance in an attempt to confront the viewer with the ways in which our governments represent – and therefore regard – the refugee. We wanted to use the technology against its intended purpose to create an immersive, humanist art form, allowing the viewer to meditate on the profoundly difficult and frequently tragic journeys of refugees.

This idea of heat, imaging heat, which we hoped would speak sideways about human displacement resulting from climate change and global warming — it also spoke more practically, even indexically, about the struggle of the refugee. Refugees literally leave the heat behind them, exposing themselves to the elements, the cold sea waves, the winter rain and the snow. Homes are replaced with tents and shelters. People die of exposure.

Light is visible heat. Light fades. Heat grows cold. People’s attention drifts. Media attention dwindles. Compassion is eventually exhausted. How do we find a way, as photographers and as storytellers, to continue to shed light on the refugee crisis, and to keep the heat on these urgent narratives of human displacement?"

— Richard Mosse, 2017

“Using a part of a weapon to figure the refugee crisis is a deeply ambivalent and political task,” Mosse says. “And building a new language around that weapon – one of compassion and disorientation, one that allows the viewer to see these events through an unfamiliar and alienating technology – is a deeply political gesture.”

Reading heat signatures of people who are completely unaware they’re being caught on camera, Mosse shows us bodies only recognisable through an intense white glow. And so we only recognise them through the context of their landscape – the great stretches of land and sea that surround them, the tent cities, the teeming boats.

Unlike the migrants that have populated our newsfeeds for the past two years, they’re shorn of facial expressions or cultural demarcations – gender, race, age or sex. “The camera I’ve used dehumanises people,” Mosse says. “Their skin glows so they look alien, or monstrous and zombie-like.

You can see their blood circulation, their sweat, their breath. You can’t see the pupils of their eyes, but a black jelly instead. But, in fact, it allows you to capture portraiture of extraordinary tenderness. We often shot at night, from miles and miles away, so we were shooting people who were not aware of being filmed.

So we captured some extremely authentic gestures – people asleep, people embracing each other, people at prayer. There’s a stolen intimacy to it. There’s no awareness, there’s no self consciousness. It’s a two-step process – dehumanising'“

Total number of migrant deaths along Mediterranean trafficking routes

4468

The top three nationalities among over one million Mediterranean Sea arrivals were

Syrian refugees (46.7%)

Afghan refugees (20.9%)

Iraqi refugees (9.4%).

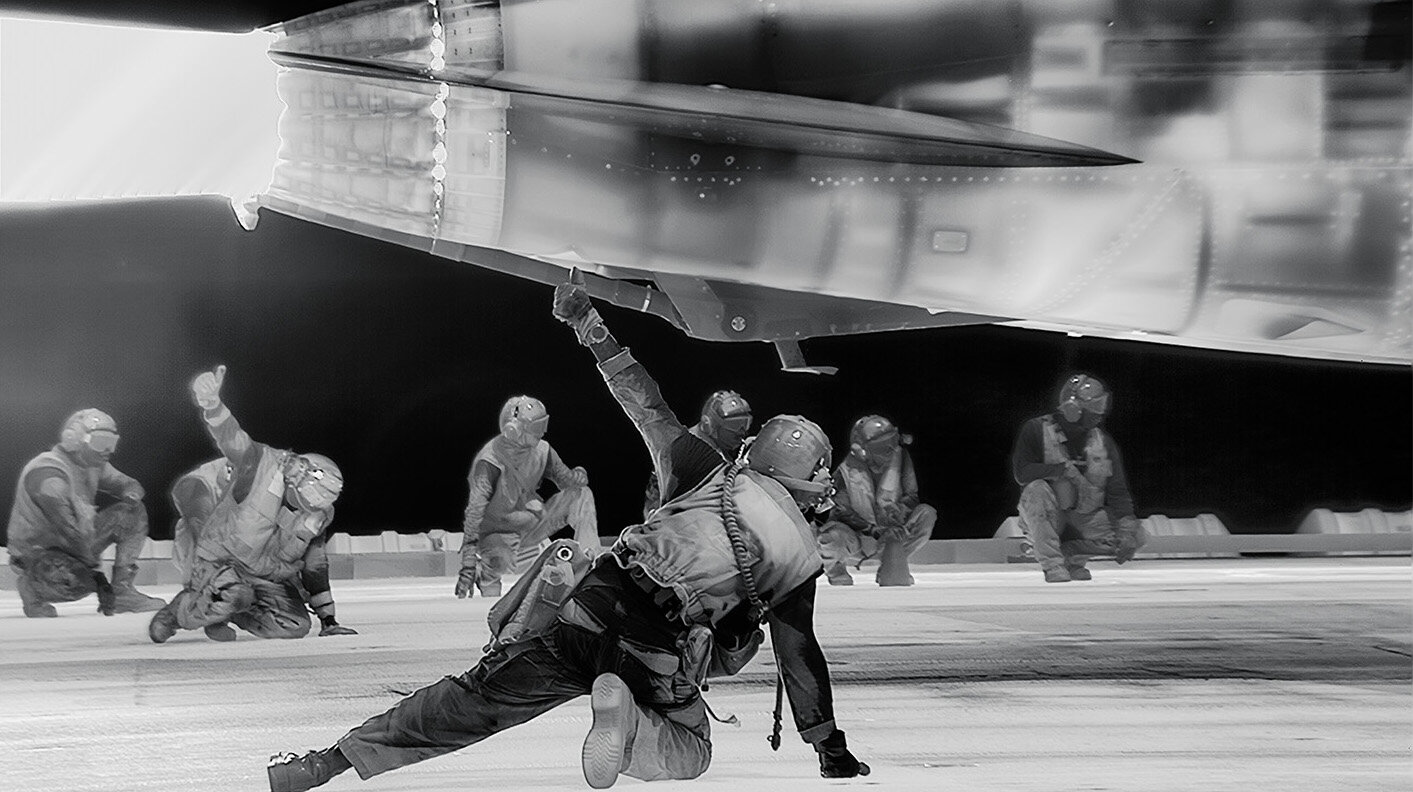

There is the spectre of violence in all forms of photography, not simply within the echo of the word shooting, but in the history of photography too, most of which has evolved directly out of military research. That’s especially the case with the technology that I chose to work with to make Incoming, which is not generally available for consumer or professional use, and has been developed and produced by a multinational defence and security company that also produces cruise missiles, drones and other technologies.

- Richard Mosse

Aboard the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt, forward deployed in the Persian Gulf to bomb IS positions in Iraq and Syria, the commander liked to remind us that the deck of the boat is “four acres of sovereign US territory.” He was wrong. It is actually four acres of dangerous metal floating in international waters.

- Richard Mosse

Outside the event in Rome, journalists waited politely as Salvini smoked and checked his phone.

"Why are you against migrants?" I asked him once he had finished his cigarette.

"I'm against illegal migrants," he corrected me. "Too many of them are dangerous for Italy and Europe."

Refugee rescue boats carrying stranded migrants face fines of up to €1m (£918,000) after the Italian parliament passed a controversial law promoted by Matteo Salvini, the far-right interior minister.

The Italian Senate, the country’s upper house, approved the law with 160 votes in favour and 57 against.

“The security decree, with more powers to police forces, more border checks and more men to arrest mafiosi, is law,” tweeted Mr Salvini, the interior minister. “I thank you, Italians, and the Blessed Virgin Mary.”

We came here to find refuge

They called us refugees

So we hid ourselves in their language

until we sounded just like them.

Changed the way we dressed

to look just like them

Made this our home

until we lived just like them.

- J.J. Bola

Last night to the flicks. All war films. One very good one of a ship full of refugees being bombed somewhere in the Mediterranean. Audience much amused by shots of a great huge fat man trying to swim away with a helicopter after him, first you saw him wallowing along in the water like a porpoise, then you saw him through the helicopters gunsights, then he was full of holes and the sea round him turned pink and he sank as suddenly as though the holes had let in the water, the audience shouting with laughter when he sank. then you saw a lifeboat full of children with a helicopter hovering over it. There was a middle-aged woman who might have been a Jewess sitting up in the bow with a little boy about three years old in her arms. The little boy was screaming with fright and hiding his head between her breasts as if he was trying to burrow right into her and the woman putting her arms round him and comforting him although she was blue with fright herself. All the time covering him up as much as possible as if she thought her arms could keep the bullets off him. Then the helicopter planted a 20 kilo bomb in among them, terrific flash and the boat went all to matchwood.

- G. Orwell

Jose Macabra

Jose Macabra was born in Toledo, Spain. With a background in psychology, he studied Digital Media and Sound Arts and Design at LCC, in London. Since graduating he has worked in various fields of the Arts, quickly becoming an established musician, curator and events promoter. After starting out with the band The Joan of Arc Family (supporting Sex Gang Children and Tuxedomoon) he went on to Performance Art, founding the group L Karma DL Trauma, which appeared at London's 291 Gallery in 2005, supporting Ron Athey’s "Judas Cradle". His personal and distinctive use of sound and image has taken him to perform in various locations around Europe; most notably in UK, Spain, Germany and Greece.

His compositions The Eye of The Beholder & London is Dead, released on The Judgement Hall Records and Black Silk Records respectively, were used to create the soundtrack for this feature by Lupus - head of The Judgement Hall Records.